The French Days

There was, however, one quite pleasant section of the town, at the northern end of the island, near a tremendous iron lighthouse that could be seen from ten miles at sea. There the houses faced onto a white coral beach. Neat and freshly painted, with green lawns and surrounding palms, they were the quarters reserved for the white Americans who ran the railroad, and it was to one of them, the home of Tracy Robinson, that de Lesseps and his family were conducted, to judge for themselves the supposed privation of life in the American tropics. Robinson, a personable and intelligent man, had spent twenty years in Panama. He was fascinated by the country, liked the people and the life, and he was certain, as he told de Lesseps, that the great future of mankind was in the tropics.

With the coming of the French, flush times began again on the Isthmus and the golden flood poured most into Colón, as the Canal diggers made their main base of operations there, unlike the Americans who struck at nature's fortifications all along the line, making their headquarters at Culebra about the center of the Isthmus. But though the French failed to dig the Canal they did win popularity on the Isthmus, and there were regretful and uncomplimentary comparisons drawn in the cafes and other meeting-places between the thrift and calculation of the Americans, and the lavish prodigality of the French. Everything they bought was at mining-camp prices and they adopted no such plan as the commissary system to save their workers from the rapacity of native shopkeepers of all sorts.

Mr. Tracy Robinson, a charming chronicler of the events of a lifetime on the Isthmus, says of this period:

"From the time that operations were well under way until the end, the state of things was like the life at 'Red Hoss Mountain' described by Eugene Field:

'When the money flowed like likker....

With the joints all throwed wide open,

and no sheriff to demur.'

"Vice flourished. Gambling of every kind and every other form of wickedness were common day and night. The blush of shame became practically unknown. That violence was not more frequent will forever remain a wonder; but strange to say, in the midst of this carnival of depravity, life and property were comparatively safe."

In the United States especially, the death toll among the French would be attributed largely to moral decadence. One of the American railroad contractors, for example, would tell a congressional committee of seeing with his own eyes piles of discarded wine bottles in Colón that were as high or higher than a two-story house. Joseph Buckin Bishop, a prim New York newspaperman who was to spend a decade in Panama, wrote that the French years had been a "genunie bacchanalian orgy." Colón was a "veritable sink of iniquity ... Champagne, especially, was comparatively so low in price that it 'flowed like water,' and ... the consequences were as deplorable as they were inevitable."

The most frequently quoted summation was by James Anthony Froude, the reigning English historian and biographer of the day, who declared that "in all the world there is not, perhaps, now concentrated in any single spot so much swindling and villany, so much foul disease, such a hideous dung-heap of moral and physical abomination as in the scene of this far-famed undertaking of ninteenth-century engineering." According to Froude the place was overrun with cardsharpers and "doubtful ladies." "Everything which imagination can conceive that is ghastly and loathsome seems to be gathered into that locality...."

As to the consumption of wine there is little doubt. It was phenomenal - and for understandable reasons. The French were accustomed to wine with meals and wine happened also to be a great deal safer to drink than the local water. The bottle dumps at Colón were every bit as high as a house. The foul alley behind Front Street was actually paved with wine bottles turned bottom-side up and became famous as "Bottle Alley." Nearly a hundred years later construction workers and amateur archaeologists would be turning up French wine bottles.

Gambling was widespread, and prostitution appears to have flourished from the start. The three most thriving industries were gambling houses, brothels, and coffin manufacturing.

Where the French did have control, the contrast was striking. Their town of Cristhope-Colomb, side by side with Colón, was neat and clean, as different as if separated by a hundred miles. The "cottages" for white technicians were as comfortable and as well constructed as conditions would allow. They were built near the water, along the eastern shoreline in what was to be a new community called Christophe-Colomb (later renamed Cristobal). They were one-story buildings, all very much alike, white with green shutters, each enclosed by verandas, and generally there was a Yucatan hammock slung at one corner of the front veranda. Everything considered, the location was ideal. At night, with a full moon flooding the white beach and a breeze coming in off the water, a young newly arrived French engineer might well find Panama all that he had dreamed.

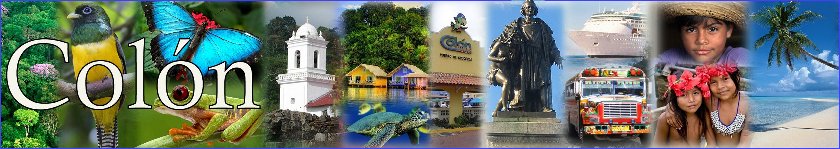

Without an architectural adornment worthy of the name, with streets of shanties, and rows of shops in which the cheap and shoddy were the rule, the town of Colón did have a certain fascination to the idle stroller. That arose from the throngs of its picturesque and parti-colored people who were always on the streets. At one point you would encounter a group of children, among whom even the casual observer would detect Spanish, Chinese, Indian and negro types pure, and varying amalgamations of all playing together in the childish good fellowship which obliterates all racial hostilities. The Chinese were the chief business people of the town and though they intermarried but little with the few families of the old Spanish strain, their unions both legalized and free, with the mulattoes or negroes were innumerable. You could see on the streets many children whose negro complexion and kinky hair combined but comically with the almond eyes of the celestial.

Public characters thronged in Colón. A town with but sixty years of history naturally abounded in early inhabitants. It is almost as bad as Chicago was a few years ago when citizens who had reached the "anecdotage" would halt you at the Lake Front and pointing to that smoke-bedimmed cradle of the city's dreamed-of future beauty would assure you that they could have bought it all for a pair of boots - but didn't have the boots. One of the figures long pointed out on the streets of Colón was an old colored man - an "ole nigger" in the local phrase - who had been there from the days of the alligators and the monkeys. He worked for the Panama Railroad surveyors, the road when completed, the French and the American Canal builders. A sense of long and veteran public service had invested him with an air of dignity rather out of harmony with his raiment. "John Aspinwall" they called him, because Aspinwall was for a time the name of the most regal significance on the island. The Poet of Panama immortalized him in verse thus:

"Oh, a quaint old moke, is John Aspinwall,

Who lives by the Dead House gate,

And quaint are his thoughts,

if thoughts at all

Ever lurk in his woolly pate,

For he's old as the hills is this coal-black man,

Thrice doubled with age is he,

And the days when his wanderings first began

Are shrouded in mystery."