First Shanty

James Stanley Gilbert

Panama Patchwork

Open Sewer

Bottle Alley

Atlantic Terminus

A Swampy Island

A major contributing factor to the economic decline in traffic around the Horn was the completion of the Panama Railroad in late January, 1855, which now made it possible to ship goods to California in three weeks time. This astounding feat of engineering was accomplished after many years of toil and a work force of thousands under the guidance of none other than William Henry Aspinwall whose farsighted vision had spurred on the era of the clipper ships with the building of the Rainbow and the Sea Witch.

The obstacles that Aspinwall faced with the building of such a railroad were formidable, the worst being the vast areas of mangrove swamps opposite Manzanillo Island, the site of the Atlantic terminal. The board of directors could not have picked a worse site, but they were forced to make their selection because George Law was determined to have a piece of the pie.

He had sent his agent, "Colonel" Albert Zwingle, down to Chagres with a large sum of money to buy or take land options on all the coastal property between Porto Bello and Navy Bay that could be used as possible terminal sites, in an attempt to bully his way on to the Panama Railroad Company board and obtain stock in the company.

Aspinwall and the board of directors resisted this strong-armed attempt and after going over old maps of the area they discovered Manzanillo Island. After a discussion, they decided that they had little choice in the matter other than to locate the terminal there on a coral-ringed 650-acre mangrove swamp surrounded by seaweed that almost disappeared at high tide. A determined effort was made to build up the island and a causeway was constructed to the mainland.

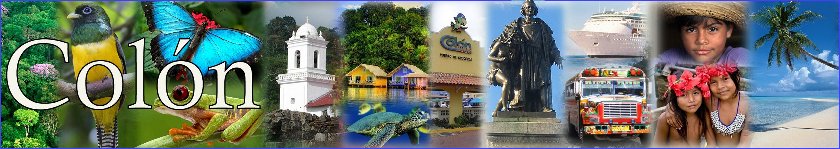

The town had been built by the railroad on Manzanillo Island, a coral flat, no more than a mile by three-quarters of a mile in area, at the entrance to Limon Bay; and so there was open salt water on all but its southern side, where a narrow channel, the Folks River, divided it from the mainland. On this swampy island, tropical vegetation had taken root, and died down to furnish soil for a new jungle until by the repetition of this process through the ages a foot or two of soil raised itself above the surface of the water and supported a swampy jungle. When the engineers first came to locate there the beginnings of the Panama railroad, they were compelled to make their quarters in an old sailing ship in danger at all times of being carried out to sea by a norther. In his "History of the Panama Railroad," published in 1862, F. N. Otis describes the site of the present city when first fixed thus:

"This island cut off from the mainland by a narrow frith contained an area of a little more than one square mile. It was a virgin swamp, covered with a dense growth of the tortuous, water-loving mangrove, and interlaced with huge vines and thorny shrubs defying entrance even to the wild beasts common to the country. In the black slimy mud of its surface alligators and other reptiles abounded, while the air was laden with pestilential vapors and swarming with sandflies and mosquitoes. These last proved so annoying to the laborers that unless their faces were protected by gauze veils no work could be done even at midday. Residence on the island was impossible. The party had their headquarters in an old brig which brought down materials for building, tools, provisions, etc., and was anchored in the bay."

The Railroad

Once construction of the railroad was begun shacks rose on piles amid the swampy vegetation of the island. At certain points land was filled in and a solid foundation made for machine shops. The settlement took a sudden start forward in 1851 when a storm prevented two New York ships from landing their passengers at the mouth of the Chagres River. The delayed travelers were instead landed at Colón, and the rails having been laid as far as Gatun, where the great locks now rise, they were carried thither by the railroad. This route proving the more expeditious the news quickly reached New York and the ships began making Colón their port. As a result the town grew as fast and as unsubstantially as a mushroom.

It was a floating population of people from every land and largely lawless. The bard of the Isthmus (James S. Gilbert) has a poem which depicts a wayfarer at the gate of Heaven confessing to high crimes, misdemeanors and all the sinful lusts of the flesh. At the close of the damning confession he whispered something in the ear of the Saint, whose brow cleared, and beaming welcome took the place of stern rejection. The keeper of the keys according to the poet cried:

"Climb up, Oh, weary one, climb up!

Climb high! Climb higher yet

Until you reach the plush-lined seats

That only martyrs get.

Then sit you down and rest yourself

While years of bliss roll on!

Then to the angels he remarked,

'He's been living in Colón!' "

The town on Manzanillo Island, still without a formal name, was generally called "Otro Lado" - "the other side" - by residents of Panama City, or sometimes "Aspinwall" in honor of the founder of the Panama Railroad Company. Even for the tropics it was a pest hole. There was no sewage disposal system or means of drainage; garbage and refuse were dumped into the streets. Privies hung over the water on the ends of the piers and docks. Since the ebb and flow of the tides never carried the waste far to sea, a vast foggy stink hung constantly over the town.