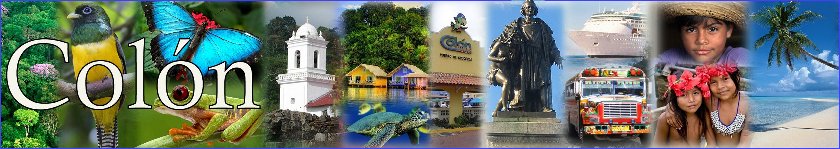

Count Ferdinand de Lesseps

Front Street

Stone Church

DeLesseps comes to Colón

The Lafayette steamed into Limon Bay under a scorching sun, and with all passengers crowding her rail, on the afternoon of December 30, 1879. On the Pacific Mail wharf a little brass band was playing mightily.

The welcoming ceremonies were held in the ship's salon, moments after she tied up. It was proclaimed an occasion second only to the arrival of Columbus in Limon Bay.jamai

After dark the town blazed with Japanese lanterns, and when the final burst of a fireworks display fell into the bay, De Lesseps came down the gangplank. Accompanied by a few friends and a small, noisy crowd - mostly ragged black children - he walked a while along Front Street, Colón's sole thoroughfare.

The following morning he was up in time to see the tropical dawn that comes all at once. With Madame de Lesseps he set off on an "inspection tour," their children, thrilled to be on solid ground again, racing ahead, climbing posts and stanchions. De Lesseps, fresh in a white linen suit, talked incessantly, concluding one remark after another with the assertinn, "The canal will be made." The upper Chagres would be turned into the Pacific, thus ending floods in the lower valley. "The canal will be made." At the great cut at the summit, the work of many thousands of men would be handled by modern explosives. "The canal will be made." He was overjoyed by the morning air. Colón was a delightful place. "The canal will be made."

Yet it is hard to conceive of his being anything but terribly disappointed by Colón. Seen from a distance, from an inbound ship, the town appeared to float on the bay as if by magic. White walls and red roofs stood out against blue water and flaming green foothills. But close up, it was a squalid shantytown set on stilts, paint peeling. There was a stone church that the railroad's guidebook made much of but that would have been of little interest anywhere else. A variety of saloons and stores lined the east side of Front Street, facing the harbor. There were an icehouse, a railroad office, a large stone freight depot, two or three seedy hotels, and the "tolerable" Washington House, a galleried white-frame affair, which, like virtually everything else in sight, belonged to the railroad company, The railroad itself ran down the middle of Front Street, and in a park, or what passed for a park, in front of the Washington House, stood an ugly red-granite monument to the railroad's founders, Aspinwall, Chauncey, and Stephens. In a nearby railroad yard there was also a bronze statue of Columbus, an Indian maiden at his side, which had been a gift from the Empress Eugenie years before. But that was the sum total of Colón's landmarks.

Streets, barely above tide level, were unpaved and strewn from end to end with garbage, bits of broken furniture, dead animals. (One French visitor would write of walking ankle-deep in "les immondices imaginables.") Enormous dark buzzards circled interminably overhead, and the human populace, most of which was black - Jamaicans, by and large, who had been brought in to build the railroad - lived in appalling squalor. Disease and poverty, hopeless, bedrock poverty as bad as any to be seen in the Caribbean, seemed to hang in the air of back streets, heavy as the atmosphere.

Compared to Colón, wrote one French journalist, the ghettos of White Russia, the slums of Toulon or Naples, would appear models of cleanliness. There were still no proper sewers in Colón, no bathrooms. Garbage and dead cats and horses were dumped into the streets and the entire place was overrun with rats of phenomenal size. And since yellow fever was understood to be a filth disease, Colón was looked upon as its prime breeding ground.

The entire town reeked of putrefaction. There was nothing to do. It was as if a western mining camp had been slapped together willy-nilly in the middle of an equatorial swamp, then left to molder and die. Once, at the height of the gold rush, there had been a kind of redeeming zest to the place, and old-timers talked of such celebrated establishments of the day as the Maison du Vieux Carri, which specialized in French girls. Now travelers disembarking to take the train dreaded spending an hour more than necessary.

There was an incident when 150 French workers, hearing of the dreadful working conditions on the Canal, refused to leave the ship "Versailles" that had brought them to Panama and the Colon police had to force them to disembark. A picture from a French newspaper shows the incident dated 29th October 1905.