In March, 1913, the author spent some time in Colón. Excellent meals were enjoyed in a somewhat old-fashioned frame hotel, while directly across the way the finishing touches were being put to a new hotel, of reinforced concrete which for architectural taste and beauty of position compares well with any seashore house in the world. At the docks were ships of every nation; cables kept us in communication with all civilized capitals. Not an insect of any sort was seen, and to discover an alligator a considerable journey was necessary. The completed Panama Railroad would carry us in three hours to the Pacific, where the great water routes spread out again like a fan. In half a century man had wrought this change, and with his great canal will doubtless do more marvelous deeds in the time to come.

At Cristobal you would be gravely taken to see the De Lesseps Palace, a huge frame house with two wings, now in the last stages of decrepitude and decay, but which you learn cost fabulous sums, was furnished and decorated like a royal chateau and was the scene of bacchanalian feasts that vied with those of the Romans in the days of Heliogabalus. At least the native Panamanian would tell you this, and if you happen to enjoy his reminiscences in the environment of a cafe you will conclude that in starting the Canal the French consumed enough champagne to fill it.

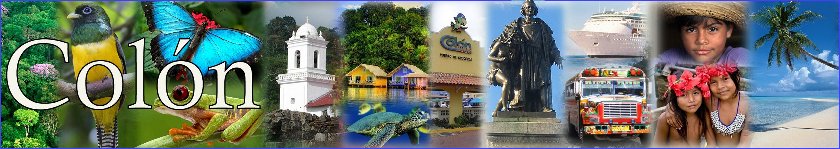

The De Lesseps house stood at what was the most picturesque point in the American town of Cristobal. Before it stood a really admirable work of art. The Bronze statue of Cristopher Columbus is of heroic size, in the attitude of protecting, with his right hand surrounding the waist of a young and beautiful Indian girl - who symbolized America - crouches by his side. With his left hand he is apparently making a gesture of appeal or explanation. The countenance is noble and benign; while the face of the Indian maiden expresses wonder, with a mixture of alarm. After the fashion of a world largely indifferent to art, the nameof the sculptor has been lost, but the statue was cast in Turin, for Empress Eugenie, who gave it to the Republic of Colombia when the French took up the Canal work, to be erected at Colon.

Buffeted from site to site, standing for awhile betwixt the tracks in a railroad freight yard, the spot on which it stands is sentimentally ideal, for it overlooks the entrance to the Canal and under the eyes of the Great Navigator, done in bronze, the ships of all the world will pass and repass as they enter or leave the artificial strait which gives substance to the Spaniard's dream.

At one time the quarters of the Canal employees - the gold employees as those above the grade of day laborers are called - were in one of the most beautiful streets imaginable. In a long sweeping curve from the border line between the two towns, they extended in an unbroken row facing the restless blue waters of the Caribbean. A broad white drive and a row of swaying cocoanut trees separated the houses from the water. The sea here is always restless, surging in long billows and breaking in white foam upon the shore, unlike the Pacific which is usually calm. Unlike the Pacific, too, the tide is inconsiderable. At Panama it rises and falls from seventeen to twenty feet, and, retiring, leaves long expanses of unsightly mud flats, but the Caribbean always plays its part in the landscape well.

Cristobal was at that time the site of the great cold storage plant of the Canal Zone, the shops of the Panama Railroad and the storage warehouses in which were kept the supplies for the commissary stores at the different villages along the line of the Canal. It possessed a fine fire fighting force, a Y. M. C. A. club, a commissary hotel, and along the water front of Colón proper, were the hospital buildings erected by the French but still maintained. Many of the edifices extended out over the water and the constant breeze ever blowing through their wide netted balconies would seem to be the most efficient of allies in the fight against disease, There was less distinct separation between the native and the American towns at this end of the railroad than at Panama-Ancon. This was largely due to the fact that a great part of the site of Colón was owned by the Panama Railroad, which in turn was owned by the United States, so that the activities of the United States government extend into the native town more than at Panama. In the latter city the hotel, the hospital and the commissary were all on American or Canal Zone soil - at Colón they were within the sovereignty of the Republic of Panama.